THE EXTINCTION OF THE ARCHITECT: THE ISSUE OF AUTHORSHIP IN THE POST-CRITICAL DESIGN PROCESS

EMMA DOHRMANN

THE CCTV HEADQUARTERS – 2012 – REM KOOLHAAS / OFFICE FOR METROPOLITAN ARCHITECTURE

ABSTRACT: Post-critical architecture can be defined as the contemporary movement that removes underpinning critique from a design. In doing so, the pragmatic considerations of architecture take centre stage, where form, skin and response to context are only the resulting factors. This design process relies heavily upon the interaction between the architect and aiding technology, which brings into question a shift in authorship. Primary analysis on the topic will be conducted through the work of Rem Koolhaas in S, M, L, XL (1995), who proposes that large scale projects have given way to post-criticality and the question of singular authorship. The investigation conducted by William J. Mitchell in The Virtual Dimension (1998) will also be utilized, as he explores the complexities that technology has imposed within architecture, such as the redefined state of authorship and the inevitable end of the architect. Additionally, the writings of other theorists such as; Christopher Brisbin, Geoffrey Broadbent, Rolf Hughes, Anthony Vidler, Ellen Upton, and Paul Virilio, will be used to support the arugment by presenting a diverse discussion on the contemporary design process. This paper consequently aims to investigate the major roles which both the architect and technology play in the contemporary design process and seeks to challenge whether technology could actually command the entire field of architecture. This research investigates specifically how Rem Koolhaas’ China Central Television Headquarters (2012) can be understood in relation to the role of the architect in the design process within the age of post-critical architecture. The themes of program, skin, context, interpretation, representation and authorship, are all brought into question by the post-critical design process which will be discussed. This paper concludes by investigating claims made by visionaries in the field, who have also questioned whether the role of an architect need exist in the near future.

The culture of critical thinking began to shift in the 1980s until a new uncritical standpoint took reign in the 2000s.1 This emergent movement has been defined as the post-critical, which can still be seen today within postmodern culture. Charles Rice describes the shift towards post-criticality as the removal of underpinning critique from any architectural design processes and decisions, meaning “architecture is free to engage with the world again”.2 This statement could be interpreted as the absence of a political viewpoint which has allowed post-critical architecture to focus instead on the substance of the design from a pragmatic perspective. However, many theorists such as Christopher Brisbin and Hal Foster argue that it instead presents a new way in which criticality can be thought of, where the aim to not be critical can be seen as a form of criticality.3 Regardless of whether post-critical projects have successfully removed all associated critique or not, this remains the main objective of post-critical architects. The recent interest in programmatic relationships can be seen as a result of new and continuously evolving technologies. Anthony Vidler claims that the use of advanced software has become less about a polemical position on involvement with the new digital world, and increasingly more about the seemingly endless limits that technology provides for design.4 This paper consequently aims to investigate the major roles which both the architect and technology play in the post-critical design process and seeks to challenge whether technology could actually command the entire field of architecture. This research investigates specifically how Rem Koolhaas’ China Central Television Headquarters (2012) can be understood in relation to the role of the architect in the design process within the age of post-critical architecture. Koolhaas has been a primary contributor to the post-critical field of architecture:

Ironically part of my reputation as a cynic is based on the more theoretical side, but if you look at the built work it’s so earnest it makes you cry how (un)cynical it is.5

This statement infers that Koolhaas was not trying to be political or opinionated and instead focused on practical issues during his recent works. One such project was the design of the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing, China, which demonstrates why this case study will be discussed in the essay to explore post-critical related themes such as; program, skin, context, interpretation, representation and authorship.

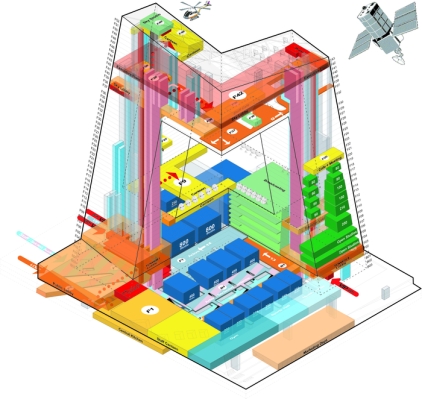

Architectural drawings are as comprehensive as a musical composition; complex to observers but easily understood by others in the field. This diagrammatic code has only grown more complex within the modern period of architecture, as designs have become more abstract, resembling seemingly random geometric forms. Therefore, Vidler refers to modern diagrams as “abstractions of abstractions”; this was viewed as the downfall of modern architecture as the built form too strongly resembled the geometry used to design it.6 However, the diagram has made a recent return to postmodernism due to an increased interest in the use and speed of digital software. The advancement of architectural software has enabled diagrammatic representations to now be celebrated as a tool to enhance programmatic relationships within designs. In other words, interest has been sparked by the ability of computer aided design that now allows for a single model to be built with all data embedded. This is dissimilar to modern architectural drawings where each plan and section were crafted individually by hand. Thus, architecture is embedded within the diagram, as the diagram is embedded in the resulting built form; Vidler suggests that postmodern architecture is now “a diagram of a diagram”.7 He mentions too that one such leading architect in the recent emergence of architecture as diagrams of diagrams can be seen to be Koolhaas.8 Koolhaas himself proposes that “Beyond a certain scale, architecture acquires the properties of Bigness”.9 This concept can be seen as the manifesto and model for post-critical architecture. A movement of architecture that could not have occurred if technology had not so rapidly reshaped the field. Similar to how the skyscraper was a result of advanced construction, materials, electrical systems and elevators. The consequences are a richer programmatic alchemy where “Bigness no longer needs the city… it is the city”.10 The CCTV Headquarters is a manifestation of both of these notions; it represents a diagram of a diagram that can be realised through its massive scale by means of technological innovations. The design for the CCTV Headquarters was born from Koolhaas’ desire to reject the recent tradition of building skyscrapers as icons. Another issue he had previously encountered was that media companies were generally designed to keep each discipline separated. To simultaneously solve both of these problems, the CCTV Headquarters was designed along a circular loop.11 This opened up not only a vertical circulation, seen in skyscrapers, but horizontal connections as well. This allowed for direct interaction between different programs and diverse spaces. The resulting external form consists of two main towers leaning towards each other at six degrees, connected both at the top and base by opposing pointed L-shape volumes.12 Therefore, the form can be seen as merely a result of programmatic needs and was a ‘criteria’ set by Koolhaas rather than an architectural gesture (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The CCTV Headquarters represented as a diagram of programmatic relationships that governed the design and resulting form.

Figure 2: An aerial view of the CCTV Headquarters, from which the resulting external form and skin can be seen.

The external skin of a post-critical building is as indifferent and unsymbolic to the design as its form. Once the program has shaped the exterior of a project the skin is then applied to this form purely as a functional element that serves to provide protection against the weather. This is true of the CCTV Headquarters where it can be seen that the skin was merely applied to the form, being a pragmatic aspect of the design (see Figure 2). The only unique difference seen in this design however, is that the skin seeks to address two functional issues; protection against the natural elements and structural support. The latter has been addressed with the application of a diagrid-bracing pattern system. Here the CCTV reveals through a display of engineering exactly where structural tensions in the design occur.13 Charles Jencks refers to this as playing “the structural truth game”, because of design choices, such as “where you don’t need the beams coming down the skin near the ground, you just subtract them”.14 However, according to Koolhaas’ concept of Bigness, the exterior of a mega scale building is dishonest. He explains that as the core and envelope increase in distance and separation in such a large project, the exterior can no longer reflect the interior of a design. The interior and exterior are now completely different projects, where the former deals with programmatic needs and the latter is an “agent of disinformation” where “what you see is no longer what you get”.15 This reflects what actually occurred during the design process of the CCTV Headquarters as Koolhaas originally planned to tilt the cores inside the building to match the exterior skin, but this wasn’t feasible due to the size of the project and the vertical support that each level required.16

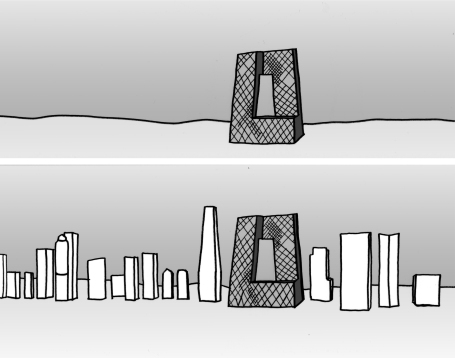

Figure 3: The CCTV Headquarters have been designed with grey glass to blend into the context of China. However, this building does not take its surrounding urban fabric into consideration, thus only responding to context in a geographical sense.

An inherent quality of Bigness is that it will always greatly impact its context, due to its sheer size. Its most radical break from architecture is that it no longer exists as a part of the city’s urban fabric, returning to Bigness as its own city as previously mentioned, “Its subtext is fuck context”.17 It has been argued that the CCTV Headquarters does respond to its context due to the incorporation of grey glass which allows it to blend into the polluted skies of China.18 However, this can be seen as a response to context in a geographical sense, rather than cultural, as the design can be seen to ignore and stand out from all surrounding city fabric (see Figure 3). Brisbin supports this statement by claiming that many western post-critical buildings have been ‘copied’ in China, which could not have occurred unless such architecture was designed without consideration of context to begin with.19 The lack of consideration for context can be seen as a consequence of post-critical architecture; large scale projects have become so large that such design decisions are out of the architect’s control. The scale of Bigness has also resulted in buildings no longer being governed by singular architectural gestures.20 However, Geoffrey Broadbent argues that a building will always carry meaning and can represent any number of diverse objects, emotions or memories. For instance, Le Corbusier designed houses in the 1920’s to be functional machines for living. Ironically these houses proved to be some of the worst in history in relation to heat loss, solar overheating, acoustics and running costs, instead these houses symbolised icons of the 1920’s. This verifies Broadbent’s claim that all architecture holds meaning in the minds of beholders, regardless of the architect’s intentions.21 Therefore, the CCTV Headquarters may not have been designed with any intended symbolism, but every viewer will have a unique encounter with the design in which a new interpretation will be perceived.

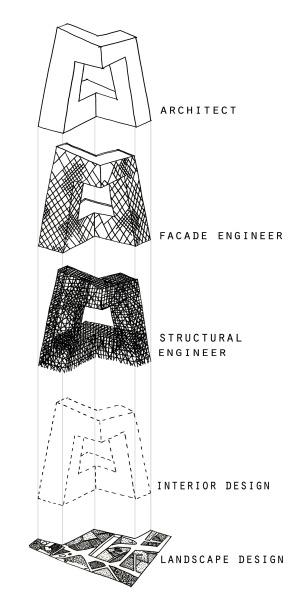

Figure 4: The role that the architect played in the design of the CCTV headquarters can be seen to extend only to the form, which was generated using computer software.

The continual advancement of digital software in architecture had led to increasingly blurred boundaries of authorship. William J. Mitchell proposes that the issue of authorship will always arise when technology is introduced to a discipline. For instance, books are mass produced, consume great amounts of raw materials and energy and are expensive sources of information, but there will always be an exact description announcing who authored and published the volume. However, it is an entirely different story now that CD-ROMs have been introduced; they are weightless and save far more trees, but can easily be transferred from CD, to a hard drive or computer and can very easily be copied and distributed. This example demonstrates a major shift in the inconclusiveness of authorship.22 Rolf Hughes supports this statement through the comparison of modern architecture authorship, during which authorship was more black and white, where society held the values of “originality, individuality, and making it new.”23 Now that technology has advanced, many major shifts in the architectural design process can be seen. One such example is the replacement of craftsmanship for computer aided design. Hand tools have been replaced by software, and the use of this software to design has meant the ability of local trade no longer defines the limits of possibilities that the architect can explore. Now all materials have “a brand name rather than a craftsman’s signature; you cannot say who created it or where.”24 The question arises of who is the author when an architect has developed a design with the assistance of a computer aided design program. In a non-linear design system, decisions are made by the system itself, which implies a responsibility for the selection of design processes. This is contradicted by the work of Heinz Von Foerster who argues that responsibility is avoided if objectivity is involved, thus machines which do not take human properties into consideration are objective and successfully elude the notion of responsibility.25 According to Koolhaas’ proposal, Bigness is beyond the control of the architect as “Bigness means to surrender to technologies; to engineers, contractors, manufacturers; to politics; to others”. Here Koolhaas argues that such a large project requires a network of other disciplines to work together as a team.26 This can be seen through the many credited roles, which include (but are not limited to) the architects, façade engineers, structural engineers, interior designers and landscape designers, who contributed towards the design process of the CCTV Headquarters (see Figure 4). Therefore, the authorship of contemporary architecture will always be up for debate, the only fact that remains clear is the architect can no longer be considered the single, heroic author.

Technology can now be seen to play a large role in the post-critical design process, especially compared to its minimal use only decades ago. This rapid acceleration at which architects are now reliant on such software has led to others in the field questioning what the future will hold for architecture and the potential of technology. After thorough research, there appears to be two categories of emerging predictions for the future of architecture; physical and virtual. The former sees advanced architecture in which technology is physically embedded, whether this is the digital systems themselves or the product of such advanced systems. Whereas the latter could be considered a more radical proposition, as it foresees the end of physical construction, producing instead a purely digital architecture. The first category has predominately arisen from interest in advancing scientific technologies. Ellen Upton suggests that architecture could represent the complexities of skin to produce ‘self-living’ buildings. She questions whether the future is heading towards nature or technology as it appears that the latter has already began to take over our society. In the past “cyborgs” were creatures to be feared, however, today these beings are our reality with the development of prosthetic limbs, hearing aids, pacemakers and digital extensions such as the Apple Watch.27 This concept is further explored by Dan Slavinsky in the recently produced series ‘In Arcadia at the End of Time’, through which he proposes the incorporation of living technology as architecture. The emergence of protocell technology could now allow for the integration of tissue and soft matter with structural systems. This process involves the manipulation of natural elements, as opposed to the use of inert building materials, in a way that could give birth to self-living buildings. This theory enables time to be a leading design element, as the scheme depends largely upon more durable architecture that grows, evolves and erodes.28 This notion is in almost complete opposition to the second, virtually conceived category of impending architecture. William J. Mitchell instead foresees a future where time is completely removed from the equation and there is a very clear distinction between material and digital;

I mean, of course, the use of immersive virtual reality to create spatial experiences that are totally separated from physical construction, mass and tactility. With this technology, you can walk or fly through virtual landscape and virtual architecture, crash through enclosing surfaces without feeling a thing, and even encounter inhabitants represented by their virtual bodies. Because there is no material to transform, there is no weathering of surfaces with the passage of time.

This electronically imagined world seems too far from reality to currently comprehend. However, Mitchell reasons that this world is almost in reach due to innovative computer aided design systems that allow a building to be virtually experienced prior to construction, and virtual reality games that demonstrate how an inhabitant could enter a digitally constructed landscape.29 This is supported by Paul Virilio who states that the invention of the elevator enabled the new architectural typology of the skyscraper, similarly, windows are currently transforming into screens on a façade, and technology will inevitably generate a new virtual architecture.30

Regardless of the infinite number of predictions that can be made for the future of architecture, most have arrived at similar conclusions; the role of the technology will eventually outweigh the role of the architect.

At one extreme, an ‘author’ would appear to have no role as such in work designed to make itself, thereby exhibiting the principle of autopoiesis or ‘self-making’. … Once the autopoetic system is up and running, the author would thereafter seem to be not so much dead (or terminally afflicted) as written out of the equation altogether.31

Hughes is already predicting that we will eventually design self-referential systems that will lead to the unemployment of all architects. In such systems, the boundary between the criteria set by the architect and the decisions made by the generative system become blurred. This is based upon the assumption that technology will continue at the same rapid rate of advancement. Virilio realises that this will be the case as he claims that matter was previously thought of as having a mass and energy, whereas, now a third dimension of ‘information’ has been introduced. Architects are currently only working with the mass and energy aspects of buildings and structure.32 This already situates the role of the architect in the past and as the importance of information increases, so will the role of technology and the need to explore virtual means of architecture; “it [architecture] will continue to exist, but in the state of disappearance”.33 Koolhaas also reaches a parallel conclusion as he suggests that “Bigness surrenders the field to after-architecture”.34 Here he is proposing that this is the last type of architecture that will be seen before the field disappears, due to advancing technologies.

In conclusion, Rem Koolhaas’ CCTV Headquarters can be seen to validate all principles of post-critical architecture. This supports the conclusion that programmatic needs govern the design of post-critical architecture (Bigness) while the external form and skin are merely resulting factors. Context is another principle that Bigness overlooks in the design process; changes may be imposed upon a design for its suitability in a location and climate, but no regard has been given to the surrounding urban fabric. These design elements suffer because post-critical architecture has become so large that many design choices are now out of the architect’s control. Any singular architectural gestures can no longer govern the design process either. This brings authorship into question because the role of the architect is now very small in relation to the many other disciples that work towards a design. It is not just the collaboration of teams that has seen the end of a singular architectural author, but the software used can also be seen to contribute to a portion of the responsibility for decisions made within the design process. This research has led to investigations conducted by others in the field, illustrating how they foresee the future of architecture. These predictions all foresee technology’s role in the design process increasing to the point that all architecture will physically be integrated with, or entirely produced by the digital realm. Predictions range from the anticipation of living architecture, where scientific technology had advanced to the point that living tissue can be incorporated as building materials, to a virtual world of architecture, where the construction process no longer exists because everything is experienced in a virtual reality. Regardless of what the future holds for architecture, most theories return to the same conclusion; the architect will have, at most, a short-term role in the future of architecture. On the other hand, it should be noted that these are merely speculations and the architect still plays a significant role in the design process of contemporary architecture. This essay aims to demonstrate the potential of the continual advancement of technology for design programs to be developed, in order to produce any range of new architectural typologies, even though it ironically could lead to the extinction of the architect in the future.

1 Hal Foster, “Post-Critical,” October 139, no. Winter (2012): 3.

2 Charles Rice, “Critical Post-Critical: Problems of Effect, Experience and Immersion,” in Critical Architecture, Critiques: Critical Studies in Architectural Humanities, ed. Jane Rendell (London: Routledge, 2007), 262.

3 Christopher Brisbin, “The Post-Critical U-Turn: A Return to Criticality through the Consumptive Affirmation of Glamour and Affect in Michael Zavros and Rem Koolhaas,” in Critique 2013: Adelaide; Conference Proceedings, (Adelaide: The University of South Australia, 2013).

4 Anthony Vidler, “Diagrams of Diagrams: Architectural Abstraction and Modern Representation,” Representations 72, no. Fall (2000):7-8.

5 Rem Koolhaas and Charles Jencks, interview by Eva Branscome, “Radical Post-Modernism and Content: Charles Jencks and Rem Koolhaas Debate the Issue,” Architectural Design 81, no. 5 (2011): 40.

6 Vidler, “Diagrams of Diagrams,” 7-8.

7 Ibid., 16-18.

8 Ibid., 3.

9 Rem Koolhaas, “Bigness, or the Problem of Large,” in S, M, L, Xl: Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large, ed. Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau (New York, U.S.A.: The Monacelli Press, 1995), 495-499.

10 Ibid., 515.

11 Clifford A. Pearson, “Too Big to Fail?” Architectural Record 200, no. 11 (2012): 87.

12 Gevork Hartoonian, Architecture and Spectacle: A Critique (UK: Ashgate, 2012), 139.

13 Hartoonian, Architecture and Spectacle, 138-139.

14 Koolhaas and Jencks, “Radical Post-Modernism and Content,” 39.

15 Koolhaas, “Bigness,” 500-501.

16 Pearson, “Too Big to Fail?” 87.

17 Koolhaas, “Bigness,” 501-502.

18 Pearson, “Too Big to Fail?” 87-88.

19 Christopher Brisbin, “”I Hate Cheap Knock-Offs!”: Morphogenetic Transformations of the ‘Culture of the Copy’ and Chinese Identity,” in Unmaking Waste 2015: Adelaide; Conference Proceedings, (Adelaide: The University of South Australia, 2015).

20 Koolhaas, “Bigness,” 499.

21 Geoffrey Broadbent, “A Plain Man’s Guide to the Theory of Signs in Architecture,” Architectural Design 7-8 (1977): 474.

22 William J. Mitchell, “Antitectonics: The Poetics of Virtuality,” in The Virtual Dimension: Architecture, Representation and Crash Culture, ed. John Beckmann (New York, U.S.A.: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 205-06.

23 Rolf Hughes, “Orderly Disorder: Post-Human Creativity,” in ACSIS: Sweden; Conference Proceedings, (Sweden: Linköping University, 2005).

24 Mitchell, “Antitectonics,” 210-212.

25 Heinz Von Foerster, Understanding Understanding (New York, U.S.A.: Springer, 2003), 293.

26 Koolhaas, “Bigness,” 513-14.

27 Ellen Upton, “Second Skin: New Design Organics,” in Entry Paradise: New Worlds of Design, ed. Gerhard Seltmann and Werner Lippert (Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2006), 122-129.

28 Dan Slavinsky, “Authorship at Risk: The Role of the Architect,” Architectural Design: Protocell Architecture 81, no. 2 (2011): 91.

29 Mitchell, “Antitectonics,” 206-209.

30 Paul Virilio, interview by Andreas Ruby, “Architecture in the Age of Its Virtual Disappearance,” in The Virtual Dimension: Architecture, Representation and Crash Culture, ed. John Beckmann (New York, U.S.A.: Princeton Architectural Press, 1998), 181-187.

31 Rolf Hughes, “The Semi-Living Author: Post-Human Creative Agency,” in Architecture and Authorship, ed. Rolf Hughes, Katja Grillner and Tim Anstey (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007), 132.

32 Virilio, “Architecture in the Age of Its Virtual Disappearance,” 180-181.

33 Ibid., 187.

34 Koolhaas, “Bigness,” 516.

FIGURES:

FIGURE 1 – OMA, orthographic diagram of CCTV Headquarters, 2002 – 2012. <http://oma.eu/projects/cctv-headquarters>, accessed 17/09/15.

FIGURE 2 – Pearson, “Too Big to Fail?” 86.

FIGURE 3 – E. Dohrmann 2015

FIGURE 4 – E. Dohrmann 2015